Mari Huws Jones

This piece originally appeared in Folding Rock Issue 001: Roots.

SOIL | 2019

Early in December 2019 I found myself doubled over and pulling wildly at the roots of nettles – shovelling soil in the shade of an elder tree, leafless in midwinter; levelling a small piece of shrubby, neglected land.

It’s a romantic idea, to move to an island and live off the land. Emyr and I had met in August the previous year. By June, the opportunity arose to become Wardens of a small, wild island, and by September there we were; limbs and spades, the soil gathering under our fingernails.

Gardening came to me like a language. Instinctively we cultivated a small piece of left-behind earth, built a polytunnel and started to grow. That first year, every seed we sowed grew. It was tropical. It was my first time experiencing the journey through the seasons as a grower – travelling through space and time, playing with heat, light and water – the miracle of what can be achieved when you have all three, soil, and a packet of seeds.

We had created a space where everything was simultaneously ancient and young at the same time. Vibrant and fleeting. The garden became a thread that tied me to time and as the years passed I almost became a puppet to its invisible strings, unconsciously playing out the rituals – sometimes, on reflection, a year exactly since the last time. Gathering and spreading seaweed, planting the first seeds, digging up the last of the potatoes. The garden taught me patience, taught me to trust, taught me that everything flowers in its own time.

I met others in the soil too; layers of past lives, stories held in old chipped pottery, glass and bone. One summer I found a flint arrowhead – it came up from the earth tangled in the roots of an onion.

My grandfather had been a gardener too and it was he who had planted a feeling deep in my childhood. He died when he was ninety-three. I wonder now what he had sown that final summer. At the time, I was a rebellious fourteen-year-old and had my lifetime again to live before I would be clipping cutting from his raspberry bushes in my own garden. This is how gardening time works; it is deep, fluid, yet rooted – it outlives us – and the feeling I’d carried from when I was five years old and digging up potatoes with him was a feeling of connection, between us and the earth

SEED | 2022

The day I found out I was pregnant, it was late August, the land tired and bone-dry after a hot summer, and I’d seen a rainbow where there shouldn’t have been one. The next twelve weeks passed in a blur of nausea and fatigue. At times I felt detached from my body, unable to comprehend what exactly was happening inside. Twelve weeks of only being able to whisper the truth into the wind had spread it thin between the blades of grass. I became startled by the thought of saying it aloud – of sharing the news with hearts and minds. In mid-October, before the winter’s path was fully blown open ahead of us, we had crossed to the mainland and I found myself lying down in a darkish room with a stranger spreading cold gel on my flat stomach. Through sound we saw our child on a small screen. Like moonlight on seawater, black, white and dancing – there it was, the unmistakable flicker of a heartbeat.

Looking back now, the thing about that winter, in the depths of it – when the days were short and the darkness heavy and pressing on our windows, when the wind had weeded in between all of the cracks and the garden was barren, I did not need to kneel in the soil with my ear to the earth to listen. I knew. I knew there was life waiting, I knew everything would return in its own time.

To have the same trust in my own body was an act of faith, not of knowing. I had not known this feeling before and at times I became focused on feeling the life within me move. Some days, a lull made me anxious, the miracle of it exposing the fragility of existence. Inside me was a soul, with a beating heart, arms and legs and hearing ears. Living on the edge of structure, far from the sliding doors of the midwives clinic, I had no choice but to have faith in my body and the land’s ability to provide.

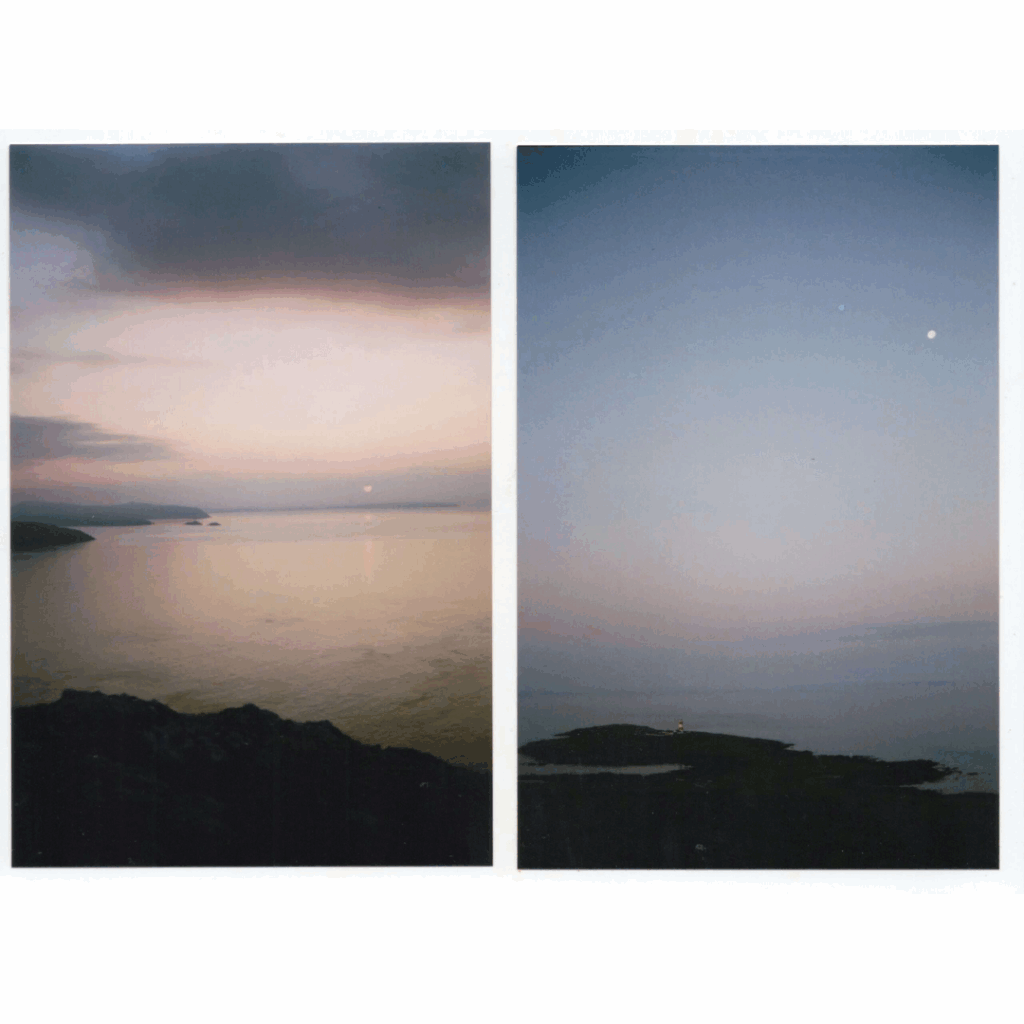

The island, Ynys Enlli, is half a mile wide and a mile and a half long. It is separated from the mainland by two miles of raging, seal-filled sea. The tide-race has shaped the history of the place. Humans have gathered on the island for thousands of years yet today, for four months of winter, it is only me and Emyr that hold the space. Off-grid, we are left to the mercy of the elements; for power and for water. The weather has a hold on our lives equal to our ancestors’.

Continue reading here.